My visit to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park started on a sunny and calm morning.

Entering this place, filled with history and emotions, puts you in a contemplative mood.

The park, with its vast green spaces and poignant monuments, offers a serene and solemn setting, conducive to reflecting on the horrors of the past and the hope for a future without war (hope keeps us alive!).

Navigating through the various sites to see, some remnants of the bomb, others statues or sculptures in tribute to the victims, leads to the Peace Museum.

The atomic bomb Dome

I started directly with the Atomic Bomb Dome, also known as Genbaku Dome. This ruined building, once the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, is one of the few structures that survived the nuclear explosion on August 6, 1945. Its skeletal, partially destroyed structure stands today as a silent yet powerful testament to past horrors.

This monument is one of Hiroshima’s most iconic sites, and its presence reminds every visitor of the devastation caused by the atomic bomb. The damaged walls, twisted metal beams, and scattered debris around the structure tell a story of destruction.

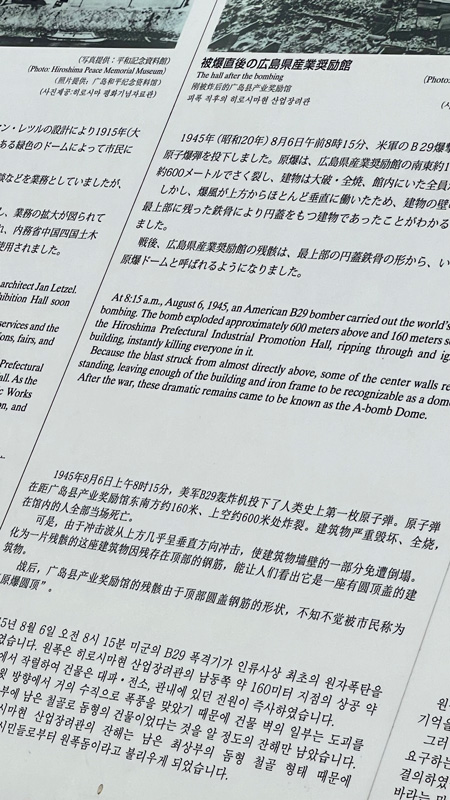

The site is surrounded by explanatory panels detailing its history and significance. Reading this information, I learned that the building was almost directly under the hypocenter of the explosion, about 600 meters above the ground. The explosion instantly killed everyone inside and nearby. Yet, miraculously, the structure itself partially survived, unlike the majority of surrounding buildings, which were completely destroyed.

Even though you can’t fully grasp it by just looking, the museum later helps you understand by showing images of the destroyed city with the dome still standing.

Today, the Genbaku Dome is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It serves as a universal symbol for peace and nuclear disarmament.

Statues and sculptures in the Peace Memorial Park

While walking through the Peace Memorial Park, I discovered many statues and sculptures that, each in their own way, add a deeper dimension to the visiting experience. These commemorative artworks are scattered throughout the park.

Starting with the “Statue of Mother and Child” which depicts a mother protecting her child from flames. There is also the “Statue of Peace,” a female figure holding a dove. Then, the “Cenotaph for the Atomic Bomb Victims” is another essential monument in the park. This simple stone arch contains a coffin with a list of all identified victims of the explosion.

Finally, the “Peace Bell” is another iconic work. Suspended in a pagoda-shaped structure, this bell can be rung by visitors, with each sound symbolizing a prayer for world peace.

These statues and sculptures, each with their own story and significance, enrich the park experience. They complement the museum’s exhibitions and the Atomic Bomb Dome, offering personal connection points and introspection for every visitor.

The peace museum

The Peace Museum, located near the dome, welcomes visitors with an exhibition on Hiroshima’s history before and after the explosion. From the first room, it sets the tone. You see a panorama of photos showing the bomb’s devastation. I held back my tears, thinking that it would only get worse. And it did. The first room presents a timeline of events leading up to that fateful day.

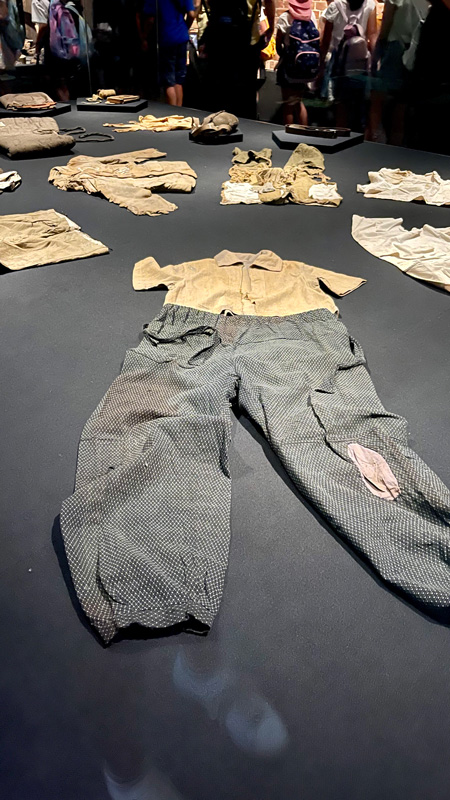

Inside, the exhibits are both educational and moving. Personal items recovered from the debris, such as burnt clothing and children’s toys, bear witness to human loss. The accounts of survivors, called hibakusha, are particularly touching.

I don’t often engage in what is called dark tourism, but some places are worth visiting to understand. I encountered many fearful looks from others during the exhibit and very few smiles, rightfully so.

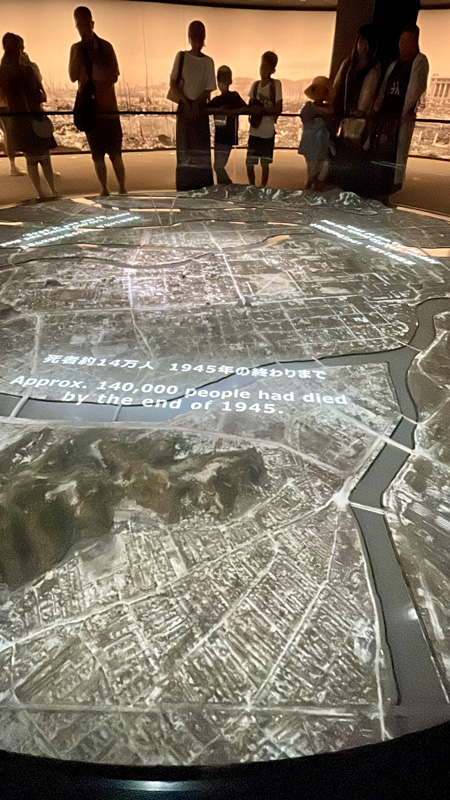

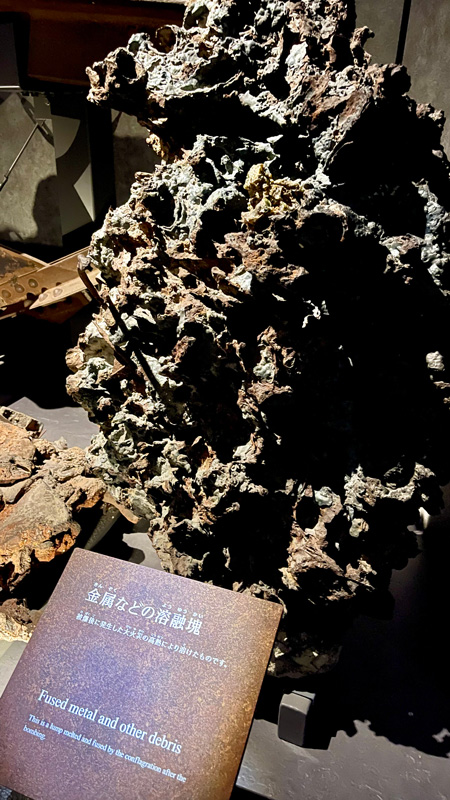

One room is dedicated to recreations of the explosion and its immediate aftermath. Models and videos show the city’s devastation and the suffering of its inhabitants. It’s a powerful visual reminder of the bomb’s impact.

I am neither a parent nor a teacher, but I saw children and school groups, and I felt sorry for them being exposed to such images at a young age. There’s even a whole exhibition of photos of corpses, with the children gathered in front. I didn’t take any photos to show you that. I shortened my visit because I didn’t feel well.

The message of peace

The museum doesn’t just recall the horrors of the past; it also conveys a message of hope and peace. Sections are dedicated to international efforts for nuclear disarmament and promoting world peace.

Leaving the museum with a heavy heart, I wondered how I would write this article and decided not to give more details than those you read because it wouldn’t serve understanding.